The world has been struggling against three “V”s or vulnerabilities to climate change, corruption and conflicts (four “C”s). However, before exhausting hope at the end of the tunnel, the world community have stood up and built the broad based global architecture in 2015 to protect the planet earth and its inhabitants.

With the alarming progression of the climate risks, the Paris Agreement was approved by 197 countries in November 2015 in the Conference of Parties (COP21) following years long negotiation under the United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Till date, 127 countries have already ratified the Paris Agreement that entered into force from November 4, 2016.

Demand-Supply gap in climate finance

Under the Paris Agreement: “Developed country parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing countries with respect to both mitigation and adaptation in continuation of their existing obligations under the convention” (Article 9.1).

The Paris Decision “strongly urges developed country parties to scale up their level of financial support, with a concrete road-map to achieve the goal of jointly providing $100 billion annually by 2020 for mitigation and adaptation” (para 115). The Decision furthermore mentions that prior to 2025, the COP shall set a new “collective quantified goal from a floor of $100bn per year” (para 54).

Pursuant to the Paris Agreement, ahead of COP22, developed countries have declared a “Road-map to $100bn” per year that projects that amount of public climate finance might be increased to $67bn in 2020 (ODI, 2016). However, the means of scaling up the adaptation finance in the absence of a time bound commitment and accurate categorisation of finance using Rio Marker and how the 50:50 balance for adaptation and mitigation will be ensured are not clear in the road-map, which are matter of concern of the developing countries.

According to the ODI report (2016), developed countries claimed that, altogether, around $33bn have been disbursed during 2014-2016, but “overall disbursement rates remain relatively low, however. Information on disbursement rates, particularly for private sector led programs, also remains incomplete.”

For ensuring transparency in external fund flow to Bangladesh, the Economic Relations Division (ERD) has already established a web-based Aid Information Management System (AIMS) but this system is yet to track the climate relevant expenditure and is also non-accessible by those who have no internet connectivity. There is a need to be proactive and for wider collaboration of ERD with all concerned stakeholders including watchdogs.

Raising voice for grant based adaptation finance

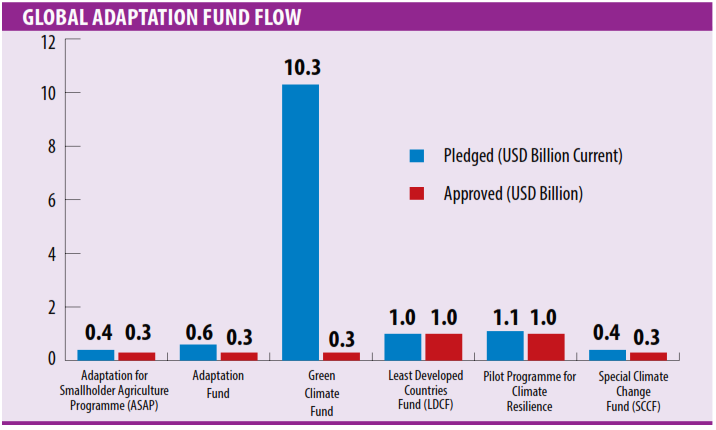

For climate change adaptation in the LDCs, at least $70-100bn per year is required, however, only $3.3bn has been so far disbursed; and of which loan captures the significant portion. It’s a matter of concern that there is no clear commitment in the Paris Agreement to mobilise required adaptation fund.

In the last six years, out of the 35 projects approved from the Green Climate Fund (GCF), only $429bn (29%) has been allocated for adaptation only — which undermined that GCF opted to maintain the 50:50 balance between mitigation and adaptation projects.

Unfortunately, there is a lack of universal definition of what counts as climate finance and that creates ambiguity regarding what qualifies as climate finance so that when countries make promises it isn’t clear what they imply.

Moreover, the GCF is open to non-public allocations or equity and loan from private entities and individuals and among the approved funds from the GCF, only 36% is grant, 28% is loan, and 36% equity. With that reality, as the most climate vulnerable country, Bangladesh should raise voice for deserving climate funds as grant as promised by developed countries in 2009 at Copenhagen.

Enhance access capacity and effective utilization of climate funds

Since there is a race among all vulnerable countries in accessing funds from the different global sources that’s why, it is required for Bangladesh to be equipped to meet the expected standards set by the GCF and other adaptation fund windows.

However, stakeholders are suggested to exert pressure upon GCF secretariat to make access procedures user-friendly and practical; and following other developing countries, Bangladesh can try to strategically use political leverage for raising funds, as and when applicable.

It is noted here that though an adaption project of $40m has been approved for Bangladesh, not a single National Implementing Entity was able to get accreditation from the GCF due to non-compliance of the standards. However, the PA apprises that developing countries including other parties have committed to that adaptation action should follow a country-driven, gender-responsive, participatory, and transparent approach that takes into account the interests of vulnerable groups, communities, and ecosystems (Article 7.5).

Regarding transparency and accountability of climate change adaptation finance, the GoB’s seventh Five Year Plan 2015 (covering 2016-2020) recognised a number of implementation challenges in climate change projects, eg lack of proper prioritisation, low fund management capacity, weaknesses in implementation and monitoring, and limited scope of sharing and learning.

In this context, MOEF has already initiated for vulnerability risk assessment and prioritisation of projects through review of the BCCSAP; and for effective monitoring of the climate funded project at ground, the 7FYP also recommended that IMED and MoEF will develop a system to encourage community participation to provide a platform for their voices and need to develop the mechanism soon.

Furthermore, the concerned staff from both the Planning Commission and the Implementation Monitoring and Evaluation Division (IMED) need to get proper capacity building along with adequate resources to assess the project proposal as well as monitoring the implemented climate financed projects properly.

It is important to note that since January 2017 the BCCRF has been officially inactive and there has been a merger between BCCTF and BCCRF to promote a “whole-of-government” in order to design an effective climate change adaptation strategy, developing a national institutional framework for allocating roles and responsibilities for different ministries were proposed in the 7FYP.

In order to ensure transparency, accountability, and integrity of all concerned climate change and climate fund governance related stakeholders — a new high-powered Climate Change Foundation (CCF)/Climate Change Trust (CCT) should be established soon in Bangladesh.

Need meaningful step

By 2030, to tackle climate change and also meet SDGs, a comprehensive integrated policy/strategy is required not only to mobilise funds from innovative sources but also to ensure meaningful transparency, accountability, participation, and integrity of all concerned stakeholders in tracking fund, planning, and monitoring the climate finance.

After all, effective climate finance is fundamental to protect lives and livelihoods of millions vulnerable people.

Originally this article was published on Thursday March 09, 2017 at Dhaka Tribune authored by The M Zakir Hossain Khan